Rheumatoid arthritis

Highlights

Drug Treatment Guidelines

Rheumatoid arthritis is best treated with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS), which include both nonbiologic and biologic medications. Current guidelines for drug treatment recommend:

- Methotrexate (Rheumatrex) or leflunomide (Arava) as initial therapy for most patients with RA

- Methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) for patients with moderate-to-high disease activity

- Methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine plus sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) for patients with poor prognostic features and moderate-to-high levels of disease activity.

- For patients with early RA (less than 3 months), anti-TNF drugs (along with methotrexate) should be prescribed only for patients with high disease activity who have never received DMARDs. For longer duration RA, anti-TNF biologic drugs are recommended for patients who have not been helped by methotrexate.

- The biologic DMARDs abatacept (Orencia) and rituximab (Rituxan) should be reserved for patients with at least moderate disease activity and poor disease prognosis who were not helped by methotrexate and other nonbiologic DMARDs.

Drug Approvals

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved as treatments for rheumatoid arthritis:

- Duexis, a combination ibuprofen/famotidine pill

- Orencia SC, a subcutaneous formulation of abatacept

Drug Warnings

The FDA is continuing to collect data to determine associations between tumor necrosis factors (TNF) blocker drugs and cancer risks. Also in 2011, the FDA added Legionionella and Listeria to the list of serious infections that pose a risk to patients who take TNF blockers. Anti-TNF drugs approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Etanercept (Enbrel)

- Infliximab (Remicade)

- Adalimumab (Humira)

- Golimumab (Simponi)

- Certolizumab (Cimzia)

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease in which various joints in the body are inflamed, leading to swelling, pain, stiffness, and the possible loss of function.

The process may develop in the following way:

- The disease process leading to rheumatoid arthritis begins in the synovium, the membrane that surrounds a joint and creates a protective sac.

- This sac is filled with lubricating liquid called the synovial fluid. In addition to cushioning joints, this fluid supplies nutrients and oxygen to cartilage, a slippery tissue that coats the ends of bones.

- Cartilage is composed primarily of collagen, the structural protein in the body, which forms a mesh to give support and flexibility to joints.

- In rheumatoid arthritis, an abnormal immune system response produces destructive molecules that cause continuous inflammation of the synovium. Collagen is gradually destroyed, narrowing the joint space and eventually damaging bone.

- If the disease develops into a form called progressive rheumatoid arthritis, destruction to the cartilage accelerates. Fluid and immune system cells accumulate in the synovium to produce a pannus, a growth composed of thickened synovial tissue.

- The pannus produces more enzymes that destroy nearby cartilage, aggravating the area and attracting more inflammatory white cells, thereby perpetuating the process.

This inflammatory process not only affects cartilage and bones but can also harm organs in other parts of the body.

Causes

The exact causes of rheumatoid arthritis are unknown. Rheumatoid arthritis is most likely triggered by a combination of factors, including an abnormal autoimmune response, genetic susceptibility, and some environmental or biologic trigger, such as a viral infection or hormonal changes.

Rheumatoid arthritis is considered an autoimmune disease. In autoimmune disorders, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys healthy cells and tissue.

The Immune Response and Inflammatory Process

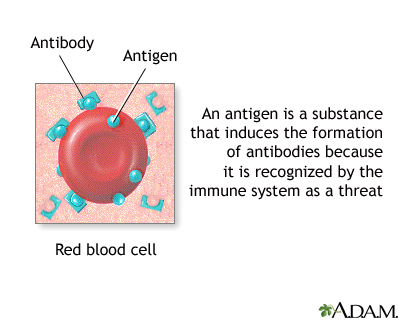

The immune system determines the body's responses to foreign substances (antigens) such as viruses and toxins. The immune response helps the body to fight infection and heal wounds and injuries. The inflammatory process is a byproduct of the immune response.

Two important components of the immune system that play a role in the inflammation associated with rheumatoid arthritis are B cells and T cells, both of which belong to a family of immune cells called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are a type of white blood cell

If the T cell recognizes an antigen as "non-self," it will produce chemicals (cytokines) that cause B cells to multiply and release many immune proteins (antibodies). These antibodies circulate widely in the bloodstream, recognizing the foreign particles and triggering inflammation in order to rid the body of the invasion.

For reasons that are still not completely understood, both the T cells and the B cells become overactive in patients with RA.

Genetic Factors

Genetic factors may play some role in RA either in terms of increasing susceptibility to developing the condition or by worsening the disease process. The main genetic marker identified with rheumatoid arthritis is HLA (human leukocyte antigen).

A number of HLA genetic forms called HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DR4 alleles are referred to as the RA-shared epitope because of their association with rheumatoid arthritis. These genetic factors do not cause RA, but they may make the disease more severe once it has developed. Genetic variations in the HLA region may also predict drug treatment response to etanercept and the disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug methotrexate.

Environmental Triggers

Infections. Although many bacteria and viruses have been studied, no single organism has been definitively identified as a trigger for RA. Higher than average levels of antibodies that react with the common intestinal bacteria E. coli have appeared in the synovial fluid of people with RA. Some researchers think they may stimulate the immune system to prolong RA once the disease has been triggered by some other initial infection. Other potential triggers include Mycoplasma, parvovirus B19, retroviruses, mycobacteria, and Epstein-Barr virus.

Risk Factors

According to the U.S. Arthritis Foundation, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects about 1.3 million Americans.

Age

Although rheumatoid arthritis can occur at any age from childhood to old age, onset usually begins between the ages of 30 - 50 years.

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is the term used for arthritis that affects children. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis often resolves before adulthood. Patients who experience arthritis in only a few joints do better than those with more widespread (systemic) disease, which is very difficult to treat. (Note: This report primarily discusses rheumatoid arthritis in adults.)

Gender

Women are more likely to develop RA than men.

Family History

Some people may inherit genes that make them more susceptible to developing RA, but a family history of RA does not appear to increase an individual's risk.

Smoking

Heavy long-term smoking is a very strong risk factor for RA, particularly in patients without a family history of the disease.

Complications

The course of rheumatoid arthritis differs from person to person. For some patients, they disease becomes less aggressive over time and symptoms may improve. Other people develop a more severe form of the disease, which can lead to serious complications that affect not only the joints but other areas of the body including organs. Fortunately, for many patients newer treatments are helping slow the progression of the disease and preventing severe disability.

Complications of rheumatoid arthritis, many of which are the result of chronic inflammation, can include:

Joint Deterioration and Pain

Affected joints can become deformed, and for some patients the performance of even ordinary tasks can become very difficult or impossible. In addition to pain, patients may also experience muscle weakness.

Peripheral Neuropathy

This condition affects the nerves, most often those in the hands and feet. It can result in tingling, numbness, or burning.

Anemia

People with RA may develop anemia, which involves a decrease in the number of red blood cells.

Eye Problems

Scleritis and episcleritis are inflammations of the blood vessels in the eye that can result in corneal damage. Symptoms include redness of the eye and a gritty sensation.

Infections

Patients with RA have a higher risk for infections, particularly if they are treated with immune-suppressing drugs (such as corticosteroids, anti-tumor necrosis factors, and disease modifying drugs).

Skin Problems

Skin problems are common, particularly on the fingers and under the nails. Some patients develop severe skin complications that include rash, ulcers, blisters (which may bleed in some cases), lumps or nodules under the skin, and other problems. In general, severe skin involvement reflects a more serious form of RA.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, loss of bone density, is more common than average in postmenopausal women with RA. The hip is particularly affected. The risk for osteoporosis also appears to be higher than average in men with RA who are over 60 years old.

Lung Disease

Patients with RA are susceptible to chronic lung diseases, including interstitial fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and other problems. Both rheumatoid arthritis itself and some of the drugs used to treat it may cause this damage.

Vasculitis

Vasculitis involves inflammation in small blood vessels and can affect many organs in the body. Manifestations of vasculitis include mouth ulcers, nerve disorders, rapid worsening of the lungs, inflammation of coronary arteries, and inflammation of the arteries supplying blood to the intestines.

Heart Disease

Patients with RA have increased risk for death from coronary artery disease. Research suggests that the chronic inflammation associated with RA may be a factor.

Lymphoma and Other Cancers

Patients with RA are more likely than healthy patients to develop non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. RA's chronic inflammatory process may play a role in the development of this cancer. Anti-TNF drugs used for RA treatment may also increase the risk for lymphoma (particularly in children and adolescents) as well as leukemia and other malignancies.

Periodontal Disease

People with RA have a higher risk for developing periodontal disease, which damages the gum and bone around the teeth.

Kidney and Liver Problems

Although rheumatoid arthritis only rarely involves the kidney, some of the drugs used to treat the disease can damage kidneys and the liver.

Pregnancy Complications

Women with RA have an increased risk for premature delivery. They are also more likely than healthy women to develop high blood pressure during the last trimester of pregnancy. For many women with RA, the disease goes into remission during pregnancy but the condition recurs and symptoms can increase in severity after giving birth.

Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of rheumatoid arthritis is morning stiffness that lasts for at least an hour. (Stiffness from osteoarthritis, in contrast, usually clears up within half an hour.) Even after remaining motionless for a few moments, the body can stiffen. Movement becomes easier again after loosening up.

Most typically, the onset of symptoms takes place over the course of weeks or even months. However, rapid onset with more severe symptoms may also occur.

Swelling and Pain

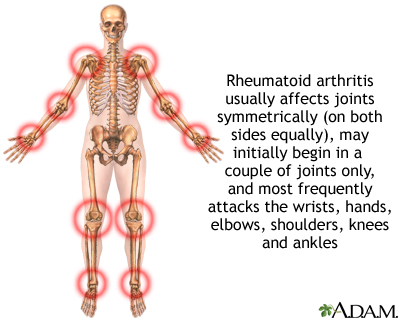

Swelling and pain in the joints must occur for at least 6 weeks before a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is considered. The inflamed joints are usually swollen and often feel warm and "boggy" (spongy) when touched. The pain often occurs on both sides of the body (symmetrically) but may be more severe on one side of the body, depending on which hand the person uses more often.

Specific Joints Affected

Although rheumatoid arthritis almost always develops in the wrists and knuckles, the knees and joints of the ball of the foot are often affected as well. Many joints may eventually be involved, including those in the cervical spine, shoulders, elbows, tips, temporomandibular joint (jaw), and even joints between very small bones in the inner ear. Rheumatoid arthritis does not usually show up in the fingertips, where osteoarthritis is common, but joints at the base of the fingers are often painful.

Nodules

In some patients with RA, inflammation of small blood vessels can cause nodules, or lumps, under the skin. They are about the size of a pea or slightly larger, and are often located near the elbow, although they can show up anywhere. Nodules can occur throughout the course of the disease, although they are usually a sign of more severe disease. Rarely, nodules may become sore and infected, particularly if they are in locations where stress occurs, such as the ankles.

Fluid Buildup

Fluid may accumulate, particularly in the ankles. In some cases, the joint sac behind the knee accumulates fluid and forms what is known as a Baker's cyst. This cyst feels like a tumor and sometimes extends down the back of the calf causing pain. Baker's cysts can also develop in people who do not have RA.

Flu-Like Symptoms

Symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and low-grade fever may also be present.

Symptoms in Children

In children, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, also known as Still's disease, is usually preceded by high fever and shaking chills along with pain and swelling in many joints. A pink skin rash may be present.

Diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis can be difficult to diagnose. Many other conditions resemble RA. Its symptoms can develop insidiously. Blood tests and x-rays may show normal results for months after the onset of joint pain.

Specific findings or presentation more likely to suggest the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis include morning stiffness, involvement of three joints at the same time, involvement of both sides of the body, subcutaneous nodules, positive rheumatoid factor, and changes in x-rays.

Blood Tests

Various blood tests may be used to help diagnose RA, determine its severity, and detect complications of the disease.

Rheumatoid Factor. In RA, antibodies in the blood that collect in the synovium of the joint are known as rheumatoid factor. In about 80% of cases of RA, blood tests reveal rheumatoid factor. It can also show up in blood tests of people with other diseases. However, when it appears in patients with arthritic pain on both sides of the body, it is a strong indicator of RA. The presence of rheumatoid factor plus evidence of bone damage on x-rays also suggests a significant chance for progressive joint damage.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate. An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR or sed rate) measures how fast red blood cells (erythrocytes) fall to the bottom of a fine glass tube that is filled with the patient's blood. The higher the sed rate the greater the inflammation. Because the sed rate can be high in many conditions ranging from infection to inflammation to tumors, the ESR test is used not for diagnosis but to help determine how active the condition is.

C-Reactive Protein. High levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) are also indicators of active inflammation. Like the ESR, a high result does not indicate what part of the body is inflamed, or what is causing the inflammation.

Anti-CCP Antibody. The presence of antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCP) can identify RA years before symptoms develop. In combination with the test for rheumatoid factor, the CCP antibody test is the best predictor of which patients will go on to develop severe RA.

Tests for Anemia. Anemia is a common complication. Blood tests determine the amount of red blood cells (hemoglobin and hematocrit) and iron (soluble transferrin receptor and serum ferritin) in the blood.

Imaging Tests

X-rays generally have not been helpful to detect the presence of early rheumatoid arthritis because they cannot show images of soft tissue. However, x-rays can help track the progression of joint damage over time. The doctor may also order other imaging tests, such as ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (dexa scans), also called bone densitometry, may be used to check for signs of bone density loss associated with osteoporosis.

Disorders with Similar Symptoms

Symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis can be mimicked by things as benign as a bad mattress or as serious as cancer. Several rare genetic diseases attack the joints. Physical injuries, infections, and poor circulation are among the many problems that can cause aches and pains. Many conditions present with symptoms of joint aches and pains. A few that in particular may be confused with rheumatoid arthritis include:

Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, but it differs from RA in several important respects:

- Osteoarthritis usually occurs in older people.

- It is located in only one or a few joints. (In fact, osteoarthritis is probably most often confused with rheumatoid arthritis if it affects multiple joints in the body.)

- The joints are less inflamed.

- Progression of pain is almost always gradual.

Gout. Gout also causes swelling and severe pain in a joint. It most commonly starts in one joint. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish chronic gout in older people from rheumatoid arthritis, since gout in this population can occur in a number of joints. A proper diagnosis can be made with a detailed medical history, laboratory tests, and detection in the affected joint of crystals called monosodium urate (MSU), which identifies gout.

Treatment

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis involves medications and lifestyle changes.

General Guidelines for Drug Treatments

Many drugs are used for managing the pain and slowing the progression of rheumatoid arthritis, but none completely cure the disease. The goals of drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Reduce inflammation

- Prevent damage to the bones and ligaments of the joint

- Preserve movement

- Help the patient be as free from side effects as possible over the long term

Drug Categories Used for Rheumatoid Arthritis

The drug classes used for RA include:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are the least potent drugs used for RA. These drugs relieve pain by reducing inflammation, but they do not affect the course of the disease.

- Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) are the main drugs used for treating rheumatoid arthritis. They slow the progression of the disease. They are much more effective than NSAIDs but also have more side effects. Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, generic) is the most widely used of these drugs.

- Biologic Response Modifiers (also known as Biologic DMARDs) are often prescribed to patients who have failed to respond to DMARDs. They may be used alone or in combination with DMARDs such as methotrexate. They modify or block destructive immune factors such as tumor-necrosis factor (TNF). Current anti-TNF drugs include infliximab (Remicade), etanercept (Enbrel), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), and certolizumab (Cimzia). Other biologic DMARDs include the interleukin-1 antagonist anakinra (Kineret), the interleukin-6 blocker tocilizumab (Actemra), the T cell co-stimulation modulator abatacept (Orencia), and rituximab (Rituxan), which targets CD20-positive B cells.

- Corticosteroids, also called steroids, are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs that are used to quickly reduce inflammation. These drugs include prednisone and prednisolone.

Treatment Approaches

The question of how early and how aggressively to treat RA has been the subject of great debate. Among patients with RA, some will go into remission and remain in remission for the length of their lives even in the absence of treatment, while others will go on to develop active, sometimes severe RA.

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) updated its classification system for rheumatoid arthritis to help identify and treat patients in earlier stages of the disease. Under the old system, patients were not diagnosed with RA until joint damage was evident. The new classification system uses a 10-point analysis that includes factors such as symptom duration, and number and size of inflamed joints.

Current practice has moved towards treating the disease aggressively while it is in its early stages to help prevent it from reaching a more severe and chronic state. Studies have found less joint damage in patients with early, aggressive treatment, particularly with the use of DMARDs and TNF modifiers in combination with methotrexate. Intensive early dosing of methotrexate may help slow progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Early combination therapy with DMARDs and corticosteroids is also showing good results.

Patients who have not been helped by one drug often benefit from a combination of drugs. However, over a longer period of time, it is not clear whether a drug combination approach offers many advantages over single drugs. It is also not certain which combination of drugs works best. Depending on your particular health condition, and how you respond to the drugs prescribed, your doctor may try various treatment strategies.

Current DMARD guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology recommend:

- Single DMARD. Methotrexate or leflunomide as initial therapy for most patients with RA

- Dual DMARD Therapy. Methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine for patients with moderate-to-high disease activity

- Triple DMARD Therapy. Methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine plus sulfasalazine for patients with poor prognostic features and moderate-to-high levels of disease activity.

- Anti-TNF DMARDs. For patients with early RA (less than 3 months), etanercept, infliximab,adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab (along with methotrexate) should be reserved only for patients with high disease activity who have never received DMARDs. For longer duration RA, anti-TNF drugs are recommended for patients who have not been helped by methotrexate.

- Other Biologic DMARDs. Abatacept, rituximab, and tocilizumab should be reserved for patients with at least moderate disease activity and poor disease prognosis who were not helped by methotrexate and other nonbiologic DMARDs.

[For more specific information on these drugs, see Medications section of this report.]

Medications

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are the standard treatments for RA. They are used either alone or in combination with newer biologic DMARDs.

DMARDs do not have any common properties other than their ability to slow down the progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Many were used for other diseases and were found accidentally to help RA. DMARDs include:

- Methotrexate (considered to be the current standard of care)

- Leflunomide

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Sulfasalazine

- Gold

- Minocycline

- Azathioprine

- Cyclosporine

Unfortunately, all DMARDs tend to lose effectiveness over time, even methotrexate. Patients rarely use one drug for more than 2 years. Combining DMARDs with each other or with drugs in other categories offers the best approach for many patients. The addition of a corticosteroid to any combination may also be helpful.

All DMARDs may produce stomach and intestinal side effects, and, over the long term, each poses some risk for rare but serious reactions. (In some cases, however, they may be less harmful than long-term NSAID treatment.)

Methotrexate. Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, generic) acts as an anti-inflammatory drug and is now the most frequently used DMARD, particularly for severe disease. Methotrexate starts working within 3 - 6 weeks, but its full effect may not occur until after 12 weeks of treatment.

Even this drug loses effectiveness, however, when used alone. For this reason, it is often used in combination with other DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalzine, or leflunomide. It may also be combined with various biological response modifier drugs, especially for treatment of patients with early aggressive arthritis. The combination appears to work better than single drug therapy.

About 20% of patients withdraw from methotrexate because of its side effects. They include nausea and vomiting, rash, mild hair loss, headache, mouth sores, and muscle aches. Methotrexate reduces levels of folic acid (folate) in the body, which can lead to some of these side effects. Doctors may prescribe folic acid supplements to prevent side effects. However, some research suggests that folic acid may interfere with methotrexate’s effectiveness.

Methotrexate is usually given as pills. Patients who need higher doses can take it as an injection. Methotrexate has fewer serious toxic effects than many DMARDs. Although these severe reactions are rare, they may include:

- Kidney and liver damage. People at particular risk for liver damage from methotrexate include those with diabetes, obesity, and alcoholism. Patients should limit alcohol consumption to no more than 2 drinks per month while taking this drug.

- Increased risk for infections. Methotrexate should not be given to patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or acute or chronic hepatitis B or C.

- Lung disease occurs in some people. People who have poor lung function are most at risk.

- The drug increases the risk for birth defects and should not be taken by pregnant women. However, methotrexate will not harm a woman’s chance for future healthy pregnancies after she stops taking the drug.

Leflunomide. Leflunomide (Arava, generic) blocks autoimmune antibodies and reduces inflammation. It also may inhibit metalloproteinases (MMP), which are involved in cartilage destruction. Leflunomide takes several weeks before improving joint pain or swelling. Full benefits may not occur until 6 - 12 weeks of treatment.

Leflunomide may be given alone or in combination with other DMARDs such as methotrexate. (This combination poses a risk for liver toxicity and requires monitoring.)

Side effects are similar to those of methotrexate, including nausea, diarrhea, hair loss, and rash. Potentially serious side effects include infections and severe liver injury. Everyone taking leflunomide should be monitored regularly, including blood tests for liver function, and anyone with liver problems should not take this drug. Leflunomide should not be taken by patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or acute or chronic hepatitis B or C.

Hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, generic) was originally used for preventing malaria and is now also used for mild, slowly progressive rheumatoid arthritis. Hydroxychloroquine starts to improve symptoms within 1 - 2 months, but it may take up to 6 months to achieve full benefit. It also does not appear to slow disease progression. Hydroxycholoroquine usually causes fewer side effects than other DMARDs. The most common side effects are nausea and diarrhea, which typically improve over time or when the drug is taken with food. Less common side effects include skin rash or bleaching or thinning of hair.

This drug used to be associated with eye and vision problems, but with current lower doses this side effect is rare. If vision problems occur, it is usually with people taking very high doses, those with kidney disease, or those over 60 years of age. Still, patients should have an eye exam (including retinal examination) within the first year of treatment. Patients with health risks (liver disease, retinal disease, over age 60) should have an annual eye exam. Patients should notify their doctors if they experience any sudden changes in vision.

Sulfasalazine. Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine, generic) works best when the disease is confined to the joints. Symptom relief occurs within 1 - 3 months.

Side effects are common, particularly stomach and intestinal distress, which usually occur early in the course of treatment. (However, serious gastrointestinal side effects, such as stomach ulcers, occur less frequently with sulfasalazine than with NSAIDs.) A coated-tablet form may help reduce side effects. Other side effects include skin rash and headache. Sulfasalazine increases sensitivity to sunlight. Be sure to wear sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher) while taking this drug. People with intestinal or urinary obstructions or who have allergies to sulfa drugs or salicylates should not take sulfasalazine.

Gold. Gold has been a time-honored DMARD for rheumatoid arthritis, although its use has decreased with the development of disease modifying and biologic drugs. Gold is usually administered in an injected form because the oral form, auranofin (Ridaura, generic), is much less effective. There are two injectable forms of gold: Gold sodium thiomalate (Myochrysine, generic) and aurothioglucose (Solganal, generic). It can take 3 - 6 months before injections have an effect on RA symptoms.

Gold injections cause mouth sores in about a third of patients. Skin side effects, including itching and rash, can be severe in some patients. The most serious side effects of gold injections, while rare, are kidney damage and decreased white blood cell count. Gold injections are usually not given to pregnant women. It is not definite that gold causes birth defects, but doctors generally recommend women use birth control while receiving this drug.

Minocycline. Minocycline (Minocin, generic) is a tetracycline antibiotic that is generally reserved for patients with mild RA. It can take 2 - 3 months before symptoms begin to improve and up to a year for full benefit. Side effects include upset stomach, dizziness, and skin rash. Long-term use of minocycline can cause changes in skin color, but this side effect usually disappears once the medication is stopped. Minocycline can cause yeast infections in women. It should not be used by women who are pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant. Minocycline increases sensitivity to sunlight and patients should be sure to wear sunscreen. In rare cases, minocycline can affect the kidneys and liver.

Azathioprine. Azathioprine (Imuran, generic) suppresses immune system activity. It takes 6 - 8 weeks for early symptom improvement and up to 12 weeks for full benefit. Azathioprine can cause serious problems with the gastrointestinal tract. About 10 - 15% of patients experience nausea and vomiting, often accompanied by stomach pain and diarrhea. (Taking the medication twice daily, instead of once daily, or taking it after eating may help avoid this problem.) Azathioprine can also cause problems with liver function and pancreas gland inflammation, and can reduce white blood cell count.

Cyclosporine. Like azathioprine, cyclosporine (Sandimmune, Neoral, generic) is an immunosuppressant. It is used for people with RA who have not responded to other drugs. It can take a week before symptoms improve and up to 3 months for full benefit. The most serious and common side effects of cyclosporine are high blood pressure and kidney function problems. While kidney function usually improves once the drug is stopped, mild-to-moderate high blood pressure may continue. Cyclosporine can also cause gout or worsen gout in people who have this condition.

Other common side effects include headache, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain and upset, and swelling of hands and feet. About 10% of patients who take cyclosporine develop tremors, increased hair growth, muscle cramps, and numbing or tingling in hands and feet (neuropathy). Swelling of the gums is also common. Patients should practice good dental hygiene, including regular brushing and flossing.

Biologic Response Modifiers (Biologic DMARDs)

Biologic response modifiers are drugs made from living cells. These drugs target specific components of the immune system that contribute to the joint inflammation and damage that are part of the rheumatoid arthritis disease process.

Biologic DMARDs are generally used to treat moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Some of these drugs are used as first-line treatments for RA. Others are used for patients who have not responded to DMARDs or other types of treatment. Depending on the specific drug, they may be used alone or in combination with the DMARD methotrexate. However, biologic response modifiers are not used in combination with each other, as this can lead to serious infections.

As with other rheumatoid arthritis drugs, these drugs do not cure the disease but can help slow progression and joint damage.

Anti-TNF Drugs. Most biologic DMARDs are anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs. They block TNF, which is a cytokine involved in the inflammatory process. Anti-TNF drugs approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis are:

- Etanercept (Enbrel)

- Infliximab (Remicade)

- Adalimumab (Humira)

- Golimumab (Simponi)

- Certolizumab (Cimzia)

Other Biologic DMARDs. Other biologic DMARDs approved for RA treatment are:

- Anakinra (Kineret) targets interleukin-1 (IL-1), another type of immune factor.

- Tocilizumab (Actemra) blocks interleukin-6 (IL-6) and is approved for patients who have not responded to anti-TNF drugs.

- Abatacept (Orencia) is a T cell co-stimulation modulator, which blocks T cell activation.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) targets CD20-positive B cells and blocks their activation.

Side Effects and Complications. Etanercept, adalimumab, anakinra, golimumab, certolizumab, and abatacept come in pre-filled syringes and are given by injection under the skin (subcutaneous injection). This may cause pain at the injection site. To prevent injection reactions, patients are sometimes pretreated with betamethasone, a corticosteroid drug, but some research suggests that the steroid does little good.

Infliximab, tocilizumab, abatacept and rituximab are given by intravenous infusion in a doctor's office. Common infusion reactions include headache, nausea, and flu-like symptoms. Because biologic response modifiers affect the immune system, patients who take these drugs have an increased risk for infections.

Biologic DMARDs should not be taken by patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or active or chronic hepatitis B or C. In addition, anti-TNF drugs should not be given to patients with a history of heart failure, a history of lymphoma, or who have multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating disorders.

Other risks associated with these drugs include:

- Anti-TNF drugs (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab) have been associated with sepsis (blood infections), pneumonia, tuberculosis, and other opportunistic and invasive fungal, bacterial, and viral infections. Other risks include non-melanoma skin cancer, lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkins lymphoma), and other malignancies; lupus; heart failure; blood disorders (including aplastic anemia); psoriasis; lung disease; and liver damage. These drugs may increase the risk for lymphoma (such as Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s) and other cancers, particularly when given to children and adolescents. They may also increase the risk for leukemia in patients of all ages.

- Abatacept should be used cautiously in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) as it may increase the risk for respiratory complications.

- Rituximab has been associated with cases of a rare and deadly brain disease called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). It also may cause hepatitis B reactivation, viral infections, and heart rhythm disturbances and other heart problems.

Corticosteroids (Steroids)

Corticosteroids work rapidly to control inflammation and pain. Long-time use, however, can have severe adverse effects. Still, they are often used under the following conditions:

- Oral corticosteroids, such as prednisolone and prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, generic), are most often used in combination with DMARDs, which significantly enhances the benefits of DMARDs.

- Oral corticosteroids are sometimes used in early stage-RA for patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs.

- Higher doses of corticosteroids are used for flareups of vasculitis and severe reactions to medications.

- Corticosteroids may be used during pregnancy to avoid exposure to more toxic drugs.

- Daily, low-dose corticosteroids are also needed in some patients to control their rheumatoid arthritis symptoms. (However, even low-dose oral steroids have adverse effects on bone density, blood sugar, and weight.)

- Corticosteroids are sometimes injected directly into joints for relief of flare-ups when only one or a few joints are affected. Doctors recommend no more than three or four injections into a specific joint a year.

Side Effects of Oral Corticosteroids. Serious side effects are associated with long-term use of oral steroids. (Low doses may reduce these risks, but they do not eliminate them.) Osteoporosis is a common and particularly severe long-term side effect of prolonged steroid use. Other adverse effects include cataracts, glaucoma, diabetes, fluid retention, susceptibility to infections, weight gain, hypertension, capillary fragility, acne, excess hair growth, wasting of the muscles, menstrual irregularities, irritability, insomnia, and, rarely, psychosis. Recent research suggests that prednisone may increase the risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer.

Withdrawal from Long-Term Use of Oral Corticosteroids. Long-term use of oral steroid medications suppresses secretion of natural steroid hormones by the adrenal glands. After withdrawal from these drugs, this adrenal suppression persists and it can take the body a while (sometimes up to a year) to regain its ability to produce natural steroids again. There have been a few cases of severe adrenal insufficiency that occurred when switching from oral to inhaled steroids, which, in rare cases, has resulted in death.

No one should stop taking any steroids without consulting a doctor first, and if steroids are withdrawn, regular follow-up monitoring is necessary. Patients should discuss with their doctor measures for preventing adrenal insufficiency during withdrawal, particularly during stressful times, when the risk increases.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Two-thirds of people with RA rank pain as their primary reason for seeking professional help. The most common pain relievers for RA are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs block prostaglandins, the substances that dilate blood vessels and cause inflammation and pain. There are dozens of NSAIDs:

- Over-the-counter NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), ketoprofen (Actron, Orudis KT, generic).

- Prescription NSAIDs include prescription forms of ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen, flurbiprofen (Ansaid, generic), diclofenac (Voltaren, generic), and tolmetin (Tolectin, generic). Meloxicam (Mobic, generic) is approved specifically for the management and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Duexis is a pill that combines ibuprofen and the H2 blocker famotidine (Pepcid, generic) that is also approved specifically for rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis.

Studies suggest that the best times for taking an NSAID may be after the evening meal and then again on awakening. RA symptoms increase gradually during the night, reaching their greatest severity at the time of awakening. Taking NSAIDs with food can reduce stomach discomfort, although it may slow the pain-relieving effect.

Long-term, regular use of NSAIDs (with the exception of aspirin) can increase the risk for heart attack, especially for people who have a heart condition. Long-term use of NSAIDs also increases the risk of ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding. To reduce the risks associated with NSAIDs, take the lowest dose possible for pain relief.

Other possible side effects of NSAIDs may include:

- Upset stomach

- Dyspepsia (burning, bloated feeling in pit of stomach)

- Drowsiness

- Skin bruising

- High blood pressure

- Fluid retention

- Headache

- Rash

- Reduced kidney function

COX-2 Inhibitors (Coxibs). Coxibs inhibit an inflammation-promoting enzyme called COX-2. This drug class was initially thought to provide benefits equal to NSAIDs but cause less gastrointestinal distress. However, following numerous reports of heart problems, skin rashes, and other adverse effects, the FDA re-evaluated the risks and benefits of COX-2 inhibitors. This led to the removal of rofecoxib (Vioxx) and valdecoxib (Bextra) from the United States market. Celecoxib (Celebrex) is still available, but patients should ask their doctor whether the drug is appropriate and safe for them.

Surgery

Some people with RA benefit from joint surgery. Surgery can help relieve joint pain, correct deformities, and modestly improve joint function. There are several types of joint surgery techniques. [For more information on surgical procedures, see In-Depth Report #35: Osteoarthritis.]

Synovectomy

Synovectomy is removal of the joint lining (synovium). It is used to remove inflamed tissue that causes pain. Synovectomy can help reduce swelling and slow the progression of joint damage.

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is performed to clean out bone and cartilage fragments (a process called debridement) that cause pain and inflammation. It is usually performed on the knee, but it also may be done on other joints:

- The surgeon makes a small incision and injects a sterile solution to make the joint swell for easier viewing.

- A lighted tube, called an arthroscope (which enables the surgeon to view the joint), is then inserted through another small incision.

- Through a third incision, the surgeon trims, shaves, or stitches the damaged tissue. (Arthroscopy is most successful when the removal of cartilage only, and not bone, is involved.)

In many cases, the procedure can be done using local anesthetic, and the patient can go home within a day. In the case of knee operations, patients can resume mild activity in a couple of days, but full recovery can take up to 3 months.

Joint Replacement (Arthroplasty)

Eventually, even after these procedures, rheumatoid arthritis may progress to the point that normal functioning is impossible. In such cases, artificial (prosthetic) replacement joint implants may be considered for shoulders, knees, hips, ankles, wrists and hands, or other joints. Joint replacement (arthroplasty) is usually reserved for people over age 50 or those whose joint damage is rapidly progressing. The joint replacement typically lasts for 20 years or more.

Joint Fusion (Arthrodesis)

If the affected joint cannot be replaced, surgeons can perform a procedure called arthrodesis that eliminates pain by fusing the bones together. However, fusing the bones makes movement of the joint impossible. Bone fusion is most often done in the spine and in the small joints of the hands (wrists, fingers) and feet (ankles, toes).

Lifestyle Changes

Exercise

It is important for patients with RA to maintain a balance between rest (which will reduce inflammation) and moderate exercise (which will relieve stiffness and weakness). Studies have suggested that even as little as 3 hours of physical therapy over 6 weeks can help people with RA, and that these benefits are sustained.

The goal of exercise is to:

- Maintain a wide range of motion

- Increase strength, endurance, and mobility

- Improve general health

- Promote well-being

In general, doctors recommend the following approaches:

- Start with the easiest exercises, stretching and tensing of the joints without movement.

- Next, attempt mild strength training.

- The next step is to try aerobic exercises. These include walking, dancing, or swimming, particularly in heated pools. Avoid heavy impact exercises, such as running, downhill skiing, and jumping.

- Tai chi, which uses graceful slow sweeping movements, is an excellent method for combining stretching and range-of-motion exercises with relaxation techniques. It may be of particular value for elderly patients with RA.

A common-sense approach to exercise is the best guide:

- If exercise is causing sharp pain, stop immediately.

- If lesser aches and pains continue for more than 2 hours afterwards, try a lighter exercise program for a while.

- Using large joints instead of small ones for ordinary tasks can help relieve pressure, for instance, closing a door with the hip or pushing buttons with the palm of the hand.

Diet

Many patients with RA try dietary approaches, such as fasting, vegan diets, or eliminating specific foods that seem to worsen RA symptoms. There is little scientific evidence to support these approaches but some patients report anecdotally that they are helpful.

In recent years, a number of studies have suggested that the omega-3 fatty acids contained in fish oil may have anti-inflammatory properties useful for RA joint pain relief. The best source of fish oil is through increased consumption of fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, and herring. Fish oil supplements are another option, but they may interact with certain medications. If you are thinking of trying fish oil supplements, talk to your doctor first.

Miscellaneous Supportive Treatments

Various ointments, including Ben Gay and capsaicin (a cream that use the active ingredient in chili peppers), may help soothe painful joints.

Orthotic devices are specialized braces and splints that support and help align joints. Many such devices made from a variety of light materials are available and can be very helpful when worn properly.

Several specially designed appliances and devices are available to ease daily activities.

Alternative and Integrative Medicine

People often turn to alternative therapies or nontraditional remedies to relieve the pain of rheumatoid arthritis. Although there is no definitive evidence to support their efficacy, some alternative procedures -- such as acupuncture, massage, mineral baths (balneotherapy), relaxation techniques, biofeedback, and hypnosis -- are not harmful and may be a useful adjunct to standard treatments.

Herbal Remedies

Herbal remedies used for RA include boswellia, equisetum arvense (horsetail), devil's claw, borage seed oil, and many others. To date, no evidence supports their efficacy.

Researchers are currently conducting studies to determine if supplements extracted from the turmeric spice can help prevent joint inflammation. The Chinese medicine herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F (TwHF) is also being investigated for its anti-inflammatory properties.

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Resources

- www.niams.nih.gov -- The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- www.rheumatology.org -- American College of Rheumatology

- www.arthritis.org -- The Arthritis Foundation

- www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/cox2 -- FDA information on COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs

- www.clinicaltrials.gov -- Find a clinical trial

References

Deighton C, O'Mahony R, Tosh J, Turner C, Rudolf M; Guideline Development Group. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009 Mar 16;338:b702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b702.

Donahue KE, Gartlehner G, Jonas DE, Lux LJ, Thieda P, Jonas BL, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of disease-modifying medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):124-34. Epub 2007 Nov 19.

Firestein GS. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Harris ED, Budd RC, Genovese MC, Firestein GS, Sargent JS, Sledge CB, eds. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2005:chap 65.

Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Sieper J, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Nov;66 Suppl 3:iii2-22.

Goldberg RJ, Katz J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain. 2007 May;129(1-2):210-23. Epub 2007 Mar 1.

Harris ED Jr. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Harris ED, Budd RC, Genovese MC, Firestein GS, Sargent JS, Sledge CB, eds. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2005:chap 66.

Huizinga TW, Pincus T. In the clinic. Rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jul 6;153(1):ITC1-1-ITC1-15.

Komano Y, Tanaka M, Nanki T, Koike R, Sakai R, Kameda H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a report from the Registry of Japanese Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients for Longterm Safety. J Rheumatol. 2011 Jul;38(7):1258-64. Epub 2011 Apr 15.

Macfarlane GJ, El-Metwally A, De Silva V, Ernst E, Dowds GL, Moots RJ; Arthritis Research UK Working Group on Complementary and Alternative Medicines. Evidence for the efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Sep;50(9):1672-83. Epub 2011 Jun 6.

Mariette X, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pavelka K, Taylor P, van Vollenhoven R, Heatley R, et al. Malignancies associated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in registries and prospective observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Nov;70(11):1895-904. Epub 2011 Sep 1.

McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 8;365(23):2205-19.

Neogi T, Aletaha D, Silman AJ, Naden RL, Felson DT, Aggarwal R, et al. The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: Phase 2 methodological report. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2582-91.

O'Dell JR. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 272.

Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010 Sep 25;376(9746):1094-108.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Apr;69(4):631-7. Epub 2010 Mar 9.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, Weisman MH, Emery P. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007 Dec 1;370(9602):1861-74.

Smolen JS, Keystone EC, Emery P, Breedveld FC, Betteridge N, Burmester GR,. et al. Consensus statement on the use of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Feb; 66(2):143-50.

Thompson AE, Rieder SW, Pope JE. Tumor necrosis factor therapy and the risk of serious infection and malignancy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Jun;63(6):1479-85. doi: 10.1002/art.30310.

Yazici Y. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: we are getting there. Lancet. 2009 Jul 18;374(9685):178-80. Epub 2009 Jun 26.

|

Review Date:

2/7/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |